Alois Klíma

* 21 December 1905 Klatovy† 11 June 1980 Prague

Alois Klíma was from his childhood led to music. He began playing the violin under the direction of his grandfather, leader of the Klatovy military veterans’ band. Later he began to study piano and was taught the basics of music theory by Josef Polák, a student of Dvořák’s. He learned to play other instruments in his uncle Eduard Klíma’s brass band. He himself liked to say jokingly that he played every instrument but the bassoon. Between 1916 and 1924 he attended the Realgymnasium (secondary school with an emphasis on the natural sciences) in Klatovy. He played violin in the student orchestra, which he also conducted. He also played the violin in amateur string quartets. At nineteen, acceding to his parents’ wishes to have their son become a secondary school teacher, he went off to Prague to study at the faculty of Natural Sciences of Charles University. There he completed seven semesters concentrating on mathematics, physics, and astronomy. During his studies he earned pocket money playing the piano and violin, furthered his theoretical knowledge by attending lectures by Zdeňek Nejedlý and Josef Bohuslav Foerster, and became a regular concert-goer.

In 1931 his interest in music won out definitively with Klíma giving up his natural science studies and becoming a student at the Prague Conservatory majoring in conducting and composing. His composition teachers were Josef Křička and Jaroslav Řídký; he studied conducting with Metod Doležil and Pavel Dědeček. In 1935 he completed his studies with a graduation concert in which he conducted his own Overture for Symphonic Orchestra (Předehra pro symfonický orchestr) and Dvořák’s Othello.

Upon graduation he accepted the position of first violinist in the recently founded Prague Symphony (in Czech FOK) Orchestra, which during his last year of studies he had also conducted during their regular radio concerts. Klíma’s conducting activities from then on remained permanently connected to radio. In 1936 he was named conductor of the Košice Radio Orchestra; then between 1936 and 1938 he conducted the Ostrava Radio Orchestra; and for a short time after September 1938 he worked with the Brno Radio. From April 1939 until the end of his professional career he remained with the Prague Radio. He worked as recording director and chiefly as conductor of the radio and other orchestras.

In 1940 the Opera-Studio ensemble was founded, and Klíma along with his teacher Pavel Dědeček were its artistic directors. The repertoire consisted mainly of Czech operas, which during the German occupation served the public as a moral support. In 1943 at a time when a sizable number of workers in the arts were threatened with forced labour (Totaleinsatz), Klíma took part in the founding of the Film Orchestra (Prag-Film), in the activities of which he also participated as conductor. After the war he continued to work mostly as a radio conductor. Alois Klíma’s most important work was his twenty-year period in the position of chief conductor of the Czechoslovak Radio Symphony Orchestra.

When in 1948 Pavel Dědeček retired as professor at the conservatory, Klíma became his successor, taking over his conducting classes and serving also as professor of orchestral performance. After 1949 he also taught at the Academy of Musical Arts. His credits as professor also include a year’s work at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki. Klíma helped train a number of conductors, many of whom had very successful careers in the arts. They include Jaroslav Vodňanský, Ivan Pařík, Oliver Dohnány, Eduard Fischer, Pavel Vondruška, and Jiří Malát.

In 1974 Alois Klíma came down with a severe bout of pneumonia. After lengthy treatment he continued to teach even though his illness had severely exhausted him. He died suddenly in June of 1980 at the age of 75 of heart failure.

For his service to art he received a number of awards and prizes, including the title of Artist of Merit.

Alois Klíma as chief conductor of the Czechoslovak Radio Symphony Orchestra1951–1971

The programming of the radio symphony orchestra in the first five post-war years shows that along with its chief conductor Karel Ančerl, it was primarily Alois Klíma, who not only shared the burdens and responsibilities of an extraordinary number of demanding preparations but also contributed significantly on the concert podium to moulding the profile of the ensemble. After Karel Ančerl left to join the Czech Philharmonic, it was then quite logical that his successor in the function of chief conductor of the Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra be no one else but conductor Alois Klíma, who at that time already had the standing of a major artist supported by favourable reviews for his accomplishments with the radio orchestra. His promotion to head of the orchestra was welcomed with enthusiasm and the expectation of further development in the level of the ensemble. Alois Klíma took over the leadership of the orchestra in November of 1950, having been appointed to begin officially in January of 1951. In 1952 he was named chief conductor of the Czechoslovak Radio symphony Orchestra. He held that top function for a full twenty years, until April of 1971, thus becoming one of the longest acting heads in history of the ensemble up to that time. In all, he was employed as radio symphony conductor for 32 years.

Evidence of the excellence of Alois Klíma’s artistic work is to be found not only in the acclaim his concerts reaped both at home and abroad but also particularly in the great number of recordings in the Radio’s sound archives still today being heard in radio broadcasts. Hearing them, we admire the perfection and logic of the musical shaping and the precision in intonation and rhythm. The quantity of Klíma’s recordings is impressive. Of Antonín Dvořák’s works he recorded 5 symphonies, 4 preludes, 3 symphonic poems, 2 instrumental concertos, the oratorios Svatá Ludmila and Stabat mater, and the cantata The Spectre’s Bride along with many other works. Of Bedřich Smetana’s works, he recorded the operas The Kiss and Libuše, 4 preludes, and 3 symphonic poems. He recorded works by Zdenĕk Fibich (the opera Šárka, melodramas, symphonic poems), by Josef Bohumil Foerster (symphonies), by Josef Suk, by Vítězslav Novák, by Otakar Ostrčil, by Leoš Janáček, and by Bohuslav Martinů. In the international repertoire he recorded 7 symphonies by Ludwig van Beethoven as well as other symphonic works and 4 instrumental concertos; he also recorded works by Hector Berlioz and Georges Bizet (Carmen); symphonies by Johannes Brahms, César Franck, Alexandr Borodin, Mikhail Glinka, Aram Khachaturian, Felix Mendelssohn, Franz Schubert, Robert Schumann, Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Igor Stravinsky, and Otakar Jeremiáš; symphonic poems by Franz Liszt; overtures by Giachino Rossini; Puccini’s opera Il tabarro; and works by Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel, Richard Wagner, Paul Hindemith, Benjamin Britten, John Ireland, and Robert Heger—all this being a small selection from all the works he performed during the time he served as chief conductor.

In an effort to present the ensemble away from the studio environment and to make it an active part of concert life, the Czechoslovak Radio Orchestra made public concerts an integral part of its job description. It was attracted by the opportunity to perform works in concert, to challenge with these public appearances other ensembles in Prague, to elicit reaction from the critics. Alois Klíma speaks in one interview of the necessity of appearing in public more often: “A person can get used to anything, even to having to perform in red light, without any audience, as if only for the four walls. And it’s all the more difficult for us in that we don’t have the ceremony and stimulation that a conductor has in the concert hall, a situation that compels him to his greatest tension, sometimes even to improvisation. Concert work, I believe, also has a greater influence on the orchestra. Its performance too is influenced by the reaction of the audience. It is for that reason that we appear ever more frequently in public and present concerts directly. I can also feel this difference between work in the studio and in the concert hall from all my experience with concerts with our own best orchestras and about 22 foreign ones.” (Žilka, V.: Lidová demokracie, 13 December 1969).

His concert programming regularly found room to include contemporary Czech works, 50 such works having been heard during Klíma’s tenure in their original premieres. He also performed word by contemporary foreign composers (Schafer, Pascal, Shostakovich, Sviridov, Mamiya, Schmit-Fontyn, Miyoshi, Woytowicz, Ryazunov, Mihály, Sugár, Liebermann, Nigg et al.), most of them in their Czechoslovak premieres, some even in their world premieres. The orchestra’s anniversary seasons (1956-57 and 1966-67) stood out for their inclusion of outstanding personalities as conductors and soloists but also for the repertoire of their studio recordings and public concerts. In 1956 the Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra and its chief conductor opened the Prague Spring Festival, and its magnificent performance of Smetana’s My Homeland was discussed in glowing reviews, remaining in memory for years afterwards as one of the highlights of the interpretative achievements of the orchestra and of Alois Klíma.

An important chapter in the development of the radio orchestra was the tours outside the territory of the Czech Republic, at first to Eastern European countries. After 1960, when international relations had thawed, the radio orchestra began to perform in Western European concert halls as well. Their first tour of Western Europe took place in June of 1961 with concerts in Germany, Switzerland, Italy, and France. The tour in its way turned into a celebration of the orchestra’s 35th anniversary.

The talent, artistry, and conducting abilities of Alois Klíma were so distinctive that he certainly could have made in our musical culture a far more distinctive name for himself and occupied an even higher position. That he did not do so may be due to his lack of assertiveness, a certain leisureliness, and inconsistency. In this matter certain radio mechanisms also played a part, for they determined the effectiveness, concert activities, and choice of repertoire of both orchestra and conductor. Often the position of the chief conductor proved not too strong when up against that of executive radio editors and even that of certain orchestra instrumentalists (all this partly because he was not a member of the Communist Party).

In spite of being to a certain extent hampered in that his position was subordinate to radio structures, he was however able in the guidance of the orchestra per se to assert his authority as chief conductor quite distinctly. Endowed with great artistic instinct and strengthened by the practice of his day-to-day teaching duties at the Conservatory and the AMU, he was capable of assessing perfectly the abilities and personal traits of each individual. He was able to confirm the artistic level displayed in orchestral tryouts and to improve it, and not just through his own practical work with the orchestra. He was able to assess the individual members of his orchestra even better during the rehearsals of his other fellow conductors. For these, he would come into the studio, take a seat among the woodwind players or in the back row of the strings, from where he had a perfect view and could thus judge precisely the positive and negative qualities of individuals. He was also aided in this by his own knowledge of the problematic of practically all musical instruments because he had the practical ability to play them himself. He considered a perfect knowledge of the scores fundamental in working together with instrumentalists and demanded it of them categorically. Alois Klíma had a strong personal relationship with his orchestra, calling it “my orchestra.” He was able to stand up for it as a collective as well as for its individual members. Of the post of chief conductor, he remarked, “A good conductor can never just put on his tuxedo, conduct a concert, and then go home. He has to educate an orchestra, guide it, nourish it.”

During his own preparation of new repertoire, he did not just study the score and he was not guided only by his musical feel and artistic instinct. When a certain work engaged his interest, he tried to go more deeply into it, even into the circumstances of its composition and into everything that might help him achieve an ideal performance. This was due no doubt to his broad education in music and to his interest in lectures by Zdenĕk Nejedlý, Otakar Zich, and Josef Bohuslav Foerster in the department of History of Music at Charles University, which he had heard during his studies at the faculty of Natural Sciences. His interest was focused not just on the score as a whole; prompted by his unusually lively feel for and interest in instrumentation, he pondered on the individual orchestral voices. In the radio archives one can still today find scores and whole sets of orchestral materials with Alois Klíma’s clear and detailed notes. One proof of the conductor’s perfectionism was his visits to musical archives and museums where he checked questionable passages and corrected mistakes at the sources.

Alois Klíma was by nature essentially an easy-going person and did not like unnecessary work. During rehearsals he worked with efficiency and extraordinary intensity, demanding maximum concentration and full focus on interpretive work. With his orchestral players he was uncompromising, hard even. As a former violinist himself, he knew the problematic of string playing inside out, and for that reason he concentrated mainly on the string section. Here too he achieved the highest possible results. Their full, shimmering sound was a firm foundation for the overall colour of the orchestra. With the woodwinds he worked mainly on getting clean intonation and tone quality. For especially important concerts Klíma designated by name the make-up of the various individual orchestra sections, basing his choice on the performance capabilities of the individual players. When famous guest conductors were due to arrive, he himself prepared and rehearsed the programme in advance. It often happened that he would at this phase have prepared it almost entirely. He was almost always present during the guest conductors’ rehearsals, just in case he might need to settle some problem. This boosted the orchestra’s efforts and raised its confidence.

Alois Klíma’s exceptional artistry and his conducting technique are remembered by his orchestra members but also by his students. His firm gesticulation was clearly intelligible and economical: he never conducted just for show. He did not need to speak much during rehearsals, knowing how to express himself perfectly with his hands. All the same, he did know that just a single word could inspire, could give a precise explanation of some means of expression that a performer should use. Often he concentrated on a detail, again and again coming back to it, repeating it, honing it. Work with detail was not however an end in itself; it was a means to a superior grasp of the whole. With his ability to discern individual music styles, he was able to elaborate the structural aspect of a composition to perfection. With symphonic works he concentrated most intently on the structuring of the exposition. For Klíma, one very important means of expression was a properly chosen tempo. He might for example repeat only a short section of a work many times, saying, “We have to find the right tempo.” In the public performance he was able to let himself go, leading the orchestra with firmness and certainty. Making technical perfection a matter of course allowed him most importantly to grasp the expressive and emotional aspect of a work. He was able to feel and experience a work deeply, fully identifying himself with it.

He had a striking feel for the arch of a melodic line. He knew how to guide an instrumentalist, constructing a melodic line, moulding a sound and colour picture.“It was magnificent the way Alois Klíma constructed the first movement and the way he guided it to its powerful coda, the way he infused the Adagio with warmth, the way he led the Scherzo with maximal austerity, the way he gradated the Finale with a rich rising tension and the way he waited until just before the end to unleash the full sound power of the orchestra…. His energetic and penetrating conducting makes Klíma one of those conductors who have a propensity to spirituality on the one hand and also to musicality on the other. He focuses on precision and transparent clarity. His sound pictures enclose an inner richness and are so vigorously brought to life as to do honour only to him and his musicians.” (Czech musicians. Fully packed Stadthalle C. H., Badische Neueste Nachrichten, 18 January 1966)

This is the kind of performance Klíma gave of works that inspired and captivated him. Since in its choice of works the orchestra was dependent on the radio’s broadcast programming, Klíma had to record a great number of works which did not in any way interest him. In such cases his approach was rather routine although still with an excellent feel for style. And he was quick and proficient, able quickly to find his bearings in a musical score. He was versatile, beyond his fondness for works from the Romantic period, especially Slavic ones, he was competent and at ease in conducting works from other stylistic periods. As an excellent mathematician, he had a remarkable memory, making it easy for him to perform contemporary works as well. He was a favourite conductor for concerto pieces, communicating to the soloists he accompanied his own calm and composure.

All these abilities made Alois Klíma a commonly sought-after conductor. Evidence of this is the great number of concerts which he gave with other orchestras. He conducted the Czech Philharmonic 30 times and also appeared with most other orchestras in Czechoslovakia as well as conducting 22 foreign ensembles. He also demonstrated his qualities by taking part in Prague Spring Festival concerts, where for 14 years, from 1946 to 1960, he conducted 13 concerts with various orchestras, this total being along with Ančerl’s 14 concerts the highest number of concerts conducted by any one conductor. He also achieved excellent results in his work as a teacher at the Conservatory and at the Academy of Performing Arts. In 1972-1973 he also taught abroad, at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki.

It is however Klíma’s work with the Czechoslovak Radio Symphony Orchestra in radio studios, in concert halls, and in the recording of phonograph records that can be called his life’s work. He made more than 1000 radio recordings and 65 phonograph recordings. He introduced about 100 new works by contemporary Czechoslovak and foreign composers. Between 1961 and 1970 he undertook a great number of tours around Europe with the radio orchestra, during which he did great service in the propagation of Czech musical culture.

On his 65th birthday on 21 December 1970, Klíma conducted a Czechoslovak Radio Symphony subscription concert. The press took notice by assessing the total of Klíma’s artistic activities: “Alois Klíma has behind him an enormous amount of unpretentious, honest work, thousands of kilometres of radio and related recordings, hundreds of concerts of symphonies, oratorios and contemporary music, work with many orchestras, with several generations of musicians; conductor Klíma has then done really great service to music and most of all to our Czech music at home and abroad.” (Alois Klíma conducts premiere - Lidová demokracie, 30 December 1970, author not indicated).

As Alois Klíma was celebrating his 70th birthday, Václav Holzknecht summed up his contribution to music: “As a conductor he stood out for his extraordinary musical ear and for his creative hands. His era is characterized by solid work in the new conditions of our musical life, bearing the qualities of professionalism, stylistic certainty, and technical reliability.” (Holzknecht, V.: Dobrá věc se podařila - Tvorba 14 May 1975)

When Alois Klíma left Czechoslovak Radio, there appeared only a very brief account: “On 1 April 1971 Alois Klíma, chief conductor of the Czechoslovak Radio Symphony Orchestra, Artist of Merit, retired after 35 years of artistic activity at Czechoslovak Radio. His work as a conductor at Czechoslovak Radio and in concert life in his own country and abroad represents a great era. The artistic personality of Alois Klíma has played a major part in the history of Czech Radio.” (Rozhlas 38/19, 3 September 1971, p. 22)Of Alois Klíma’s retirement from the Czechoslovak Radio Symphony Orchestra none of the daily newspapers took any notice at all!His sense of responsibility to art led Alois Klíma, after a heart attack in 1977, to cancel all the concerts he had scheduled. His last public appearance was a concert with the Czechoslovak Radio Symphony Orchestra in the Garden on the Ramparts (zahrada Na Valech), where he conducted Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances. During the last years of his life, he taught conducting and orchestra performance at the AMU in Prague. His last meeting with the Czechoslovak Radio Symphony Orchestra took place in March of 1980 when he was invited by orchestra members to a social evening, to which he was symbolically escorted by his student František Vajnar, who had in 1980 become chief of the radio orchestra following the tenure of Jaroslav Krombholc (1973 – 1979). It was a touching reunion for the conductor and his orchestra. Not long after that, on 11 June 1980, Alois Klíma died.For his long years of work, for the great number of enjoyable concerts he led, and for his outstanding recordings he has earned our thanks and a place of honour among radio conductors.

Author: Ada Slivanská

“What a pity that probably only now after his death do we realize how much higher he reached than we were able to appreciate while he was still alive. After Václav Talich, he has left a deep, very precious mark. With his artistic legacy, the most memorable moment of which is his unforgettable performance of Smetana’s My Homeland at the opening of the Prague Spring Festival in 1956, he has inscribed himself in the development of our musical culture as one of the most stimulating figures of a whole period of stylistic interpretation. In the music of Dvořák, Smetana, and Suk Klíma revealed to us an extraordinary world of moods, of happiness, of refinement and nobility, of purification that went beyond the usual frame of Romantic metaphor. It was the coalescence of deep currents, from which there emerged a single unified work. He was a genuinely Czech artist.” (Jiří Štilec: from the text on a record cover published by Panton, Smetana – Vltava, Dvořák – Eighth Symphony, Czechoslovak Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Artist of Merit Alois Klíma. Recorded by Czechoslovak Radio in Prague in 1965, published in 1980)

E-shop Českého rozhlasu

Hurvínek? A od Nepila? Teda taťuldo, to zírám...

Jan Kovařík, moderátor Českého rozhlasu Dvojka

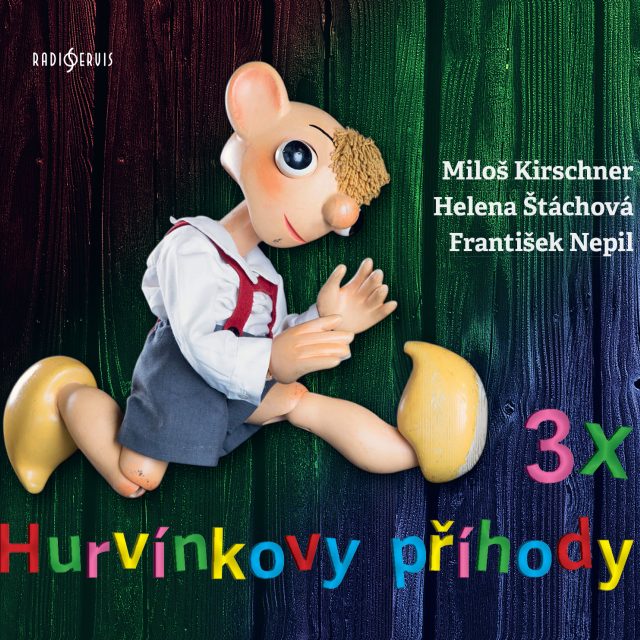

3 x Hurvínkovy příhody

„Raději malé uměníčko dobře, nežli velké špatně.“ Josef Skupa, zakladatel Divadla Spejbla a Hurvínka