Bohuslav Martinů

* 8 December 1890 Polička† 28 September 1959 Liestal (Switzerland)

The fourth in the group of classic composers that also includes Smetana, Dvořák and Janáček is Bohuslav Martinů, who ranks among the most important composers of the 20th century. His symphonic and operatic works in particular constitute a lasting fundamental contribution. Upon commission from leading European and American artists, he penned more than 400 works in all the genres of instrumental and vocal music. Virtually self-taught, Martinů continued to study and learn from scores his whole life through, creating for himself starting in the 1950s a musical language all his own, one recognizable after only a few measures. Along with his unerring feel for form, other of its basic ingredients were very disperate elements such Dvořákian melody, a fondness for 1920s American jazz, inspiration from English madrigals of the Renaissance, the strict structure of the late Baroque concerto grosso, the tonalities of French impressionism, a liking for the melodic progressions of Czech and Moravian folk songs and towards the end of his life a leaning toward the sound of so-called “New Music.” His unintendedly adventuresome life took him from the belfry of St. James in Polička, the town where he was born on 8 December 1890, through Prague, Paris and New York finally to Switzerland, where as an American citizen he died of stomach cancer in 1959.

He attained real maturity in Paris, where he had relocated in late 1923. After his String Quartet No. 2 of 1925 there followed a series of almost three hundred works, many of which have found their place in the repertoire of leading soloists, ensembles and orchestras. Among his more than one hundred chamber works these include a series of seven string quartets and five piano trios; sonatas for violin, viola, cello, flute and piano; and duos, trios, quartets, quintets, sextets, septets, octets and nonets for various combinations of instruments. His compositions for chamber orchestra include Partita, Sinfonietta La Jolla and in particular three crowning works of the late 1930s: Concerto grosso; Double Concerto for Two String Orchestras, Piano and Timpani; and Toccata e Due Canzoni. He composed whole series of solo concertos: most notably five for piano (for among others Rudolf Firkušný); four for violin (for among others Samuel Dushkin and Mischa Elman); and cello concertos (e.g., for Gaspar Cassadó and Pierre Fournier). In addition, he wrote one concerto each for viola, oboe and harpsichord.

During the deepening international crisis of the 1930s he tried to use his music to draw attention to his homeland. He took an active part in the activities of the Czechoslovak exile government in Paris. Conscious of his international importance, he remarked that his works “were at this moment far more important for us than for others, especially as I have managed to achieve a position here [in Paris], from where I can really work to propagate our art with significant results.” The invasion of France by Nazi Germany finally compelled him to emigrate to the United States.

The series of six symphonies which he composed in the United States for leading American orchestras (Boston, Philadelphia and Cleveland) placed him not only among the most important but above all among the most performed composers of his time. Along with the symphonies he worked tirelessly on the operas, the genre in which he perceived his highest ambitions to lie. We cannot in the 20th century find many composers who devoted themselves to the composition of operas (and ballets) so intensively and so systematically. Martinů wrote fourteen of them in total, and when we add to them the works planned or already partially written, there would even be many more. Already in the late 1920s he had staked out a bold design which he worked step by step to fulfil right up until his death: to rid the opera of its “psychologizing slag” and give it rules deriving from musical logic. His central idea was to complete the development of Czech musical theatre with those elements which in his opinion had been omitted by the Czech national revival. It is precisely for that reason that in the list of Bohuslav Martinů’s operas we find opera buffa (Voják a tanečnice [The Soldier and the Dancer], Alexandre bis [Alexander Twice], Mirandolina); the little one-act surrealistic play Les larmes du couteau [Tears of the Knife]; the opera-film Les Trois souhaits ou les vicissitudes de la vie (Three Wishes or the Vicissitudes of Life); a modern-age version of the medieval mystery plays in his cycle Hry o Marii (The Plays of Mary); radio operas Hlas lesa (The Voice of the Forest) and Veselohra na mostě (Comedy on the Bridge); the opera-ballet Divadlo za branou (The Suburban Theatre) deriving from the commedia dell’arte tradition; the lyrical surrealistic opera-dream Julietta (Snař) [Julietta or the Dream-Book]; the television opera The Marriage (Ženitba); the pastoral What Men Live By (Čím lidé žijí); the surrealistic drama Ariane with its musical roots in early Baroque Italian operas; and the lyrical drama The Greek Passion (Řecké pašije).

Towards the end of his life Martinů remained quite isolated, for he found himself excluded from both the political camps of those times: the communist one (then espoused by Czechoslovakia) and the one on the extreme right represented in those days by Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee. Even worse, each of these camps considered him to be a partisan of the other side. He turned into an uncomfortable “holdover” from the pre-war era, not just in politics but also in art, given that the 1950s were strongly marked by the rise of the leaders of the dogmatic generation of the Darmstadt summer courses. Proof of Bohuslav Martinů’s great moral strength is the fact that he remained forever true to the conviction he expressed during the difficult period of the signing of the Munich Agreement: “Composers of the past also lived through hard times, and yet they left after them a beautiful image of the world and life.”

After the fall of the “iron curtain,” with the autonomy of the Bohuslav Martinů Foundation, with the founding of the Bohuslav Martinů Institute and above all with the Martinů Revisited project which they initiated and coordinated to mark worldwide the 50th anniversary of the composer’s death, Martinů’s essential works have been returning with ever increasing intensity to concert halls and opera houses.

Autor: Aleš Březina

E-shop Českého rozhlasu

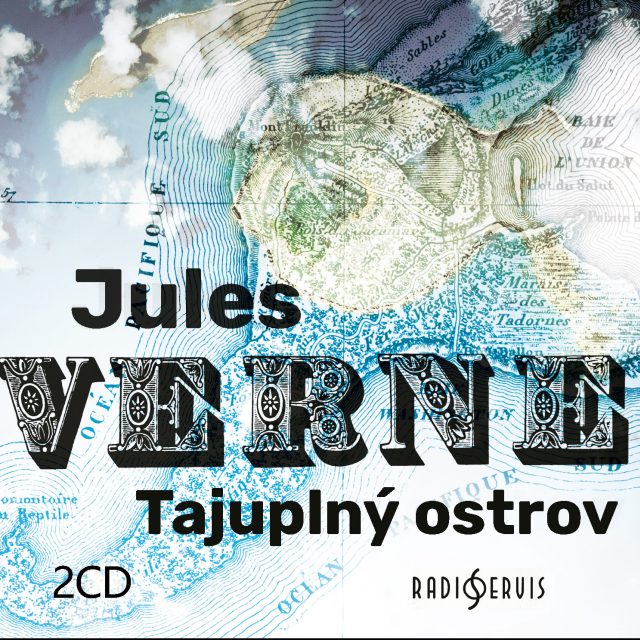

Vždycky jsem si přál ocitnout se v románu Julese Verna. Teď se mi to splnilo.

Václav Žmolík, moderátor

Tajuplný ostrov

Lincolnův ostrov nikdo nikdy na mapě nenašel, a přece ho znají lidé na celém světě. Už déle než sto třicet let na něm prožívají dobrodružství s pěticí trosečníků, kteří na něm našli útočiště, a hlavně nejedno tajemství.