Jiří Pauer

* 22 February 1919 Libušín† 21 December 2007 Prague

A distinctive personality in Czech music of the second half of the 20th century, as a composer he built on the classic line of Czech music although we also find in his works influences of many trends in new music. Among the representatives of music of the 20th century, he particularly admired Bohuslav Martinů as well as Benjamin Britten and Dmitri Shostakovich, with whom he corresponded.

He was unusually capable in leadership positions and for a number of years stood at the head of some very important Czech music institutions. As a sought-after teacher he helped educate a whole generation of successful composers.

His road to a professional career as a composer was not easy for Jiří Pauer. After studies at the Teachers’ Institute in Kladno, he taught from the age of nineteen in elementary schools. At the same time he continued his education in music privately with Otakar Šín and later at the Prague Conservatory with Alois Hába. Although Jiří Pauer’s composing career was quite different from that of the two generations older Alois Hába, they became lifelong friends. Jiří Pauer paid homage to the memory of Hába in the 1970s with one of his best works, the prelude Initials, where the basic material is formed by the notes H – A – B – A (translator’s note H = B natural in English; B = B flat).

After the Second World War ended, Jiří Pauer studied at the newly opened Academy of Musical Arts under Pavel Bořkovec. It was in these years too that Pauer’s unusual organizational abilities first became evident. Immediately after the war he founded in Prague a new municipal music school, where he worked for four years. Alois Hába brought Jiří Pauer into the organizational board of the Přítomnost (Presence) Association that fostered the newest trends in composition, in opposition to the traditionally oriented Umělecká Beseda Association (the music section of which was founded by among others Bedřich Smetana himself). After all the composer associations were gathered together into the newly founded Association of Czechoslovak Composers (Svaz skladatelů), Jiří Pauer became its foremost representative and influenced its activities with a few small exceptions virtually throughout its whole existence. In the 1950s he literally went through several institutions: the Music and Art Centre, the Ministry of Culture, and Czechoslovak Radio. Eventually the institutions central to his activities were to be the two major ensembles of Czech musical culture: the Czech Philharmonic and the National Theatre.

He served as director of the Czech Philharmonic for a full 22 years (1958–1980). One can without exaggeration call his directorship the period of the greatest rise in the reputation of this orchestra and of the ensembles and individuals connected to the Czech Philharmonic (the Czech Classical Choir, the Prague Philharmonic Children’s Choir, the Czech Nonet, the Smetana Quartet; a number of other chamber ensembles; soloists Josef Suk and Zuzana Růžičková among others). Orchestral instrumentalists still today speak with respect of how more than once he was able to protect them from various unreasonable pressures of those times and from the officials representative of those times, and how in the tuning-up room he could “haul them over the coals” when he was not happy with the artistic quality they achieved in their performances.

During two periods Jiří Pauer was head of opera at the National Theatre (1953-1955 and 1965-1967), and in his seventies he settled in for ten years as director of the entire National Theatre. In mentioning his work as an organizer we should also not forget his service on the board of the Prague Spring Festival and in the Association for the Protection of Authors’ Rights, where in the 1960s and 1970s he was always one of the main sources of information about the most recent world trends in music.

Between 1965 and 1990 Jiří Pauer taught composition at the Academy of Performing Arts (AMU) in Prague. One often heard about how much his work helped students. As a teacher he was very generous, able to empathize with the differing personalities of the individual students. He was able to assess quite exactly the qualities of a newly composed work. When such was needed, he knew how to guide students decisively in a new direction or to encourage them, whether the issue was their carelessness in certain elements of the art of composition or even their poor achievement. With virtually no exceptions, from the late 1970s his students universally made names for themselves as composers and as experts in many different positions in music institutions.

What is amazing is that with all these activities and the stress and total exhaustion they entailed, Jiří Pauer still managed to compose a great number of works, amounting to over 150 opus numbers and extending to all genres. Most important is his contribution in the area of music drama works. Those occupy an unusually significant place not only in terms of the composer’s own works but also in the national context of musical works for the theatre in the whole post-war era. Jiří Pauer had had a very positive relationship with the theatre since his youth, and his first operatic work, Žvanivý slimejš (The Garrulous Snail), was written while he was still a student (1949-50). This witty one-acter revealed the composer’s feel for the specifics of musical theatre for children and became a favourite work frequently staged in the Czechlands and abroad. Pauer’s music drama oeuvre is quite diverse as to type: it includes full-length opera of the classical type; a cycle of five operatic farces; a comic opera of the traditional buffo type; and operas, ballets, and musicals for children. It is also worth noting the fact that more than half of these works for the theatre are intended for young audiences. In every case Jiří Pauer showed unusual intuition in choosing his subject matter, a feel for stage business, and a knowledge of practical theatre. Jiří Pauer’s second opera, Zuzana Vojířová (1954-57), found remarkable favour with audiences, being one of the few operas written in modern times (if indeed not the only one!) that theatre-goers themselves actively sought out. The composer chose a story strong in emotion and stage action that was in line with his own aim of creating a full-length work that would be accessible to audiences while still continuing in the line of Czech operatic tradition.

Jiří Pauer’s symphonic works are represented mainly by his Scherzo for Orchestra from the early 1950s, by his Symphony for Large Orchestra (1963), by his symphonic picture Panychida (1969), by his Symphonic Prologue (1972), by the symphonic movement Initials (1974), and finally by his Symphony for Strings (1978). Without question one of his more noteworthy works is the monodrama for baritone and orchestra called Swan Song (1973), composed on his own text based on a one-act play by Chekhov, creating the moving confession of an elderly actor, who after his last performance remains alone and isolated on a dark stage.

Another much appreciated and sought-after group of Pauer’s compositions are his concertos: concertos for bassoon, trumpet, oboe, French horn and marimba, all of which contributed notably to the literature for those various instruments.

An unusually large part of his oeuvre consists of chamber works, player friendly pieces written with a thorough knowledge of the problematics of the individual instruments and for that reason frequently sought out by musicians. Although from the outside Jiří Pauer’s works might appear to deserve the label “traditional,” he did not shun integrating new elements into his musical language. In the 1970s, for example, he composed some serial works, albeit from his own personal perspective. He responded similarly to the music of the so-called Polish school.

Jiří Pauer lived out his last years in relative isolation, hampered by illness. Nevertheless he continued to dictate little piano pieces to his wife, who remained faithfully at his side his whole life. His creative spirit knew no rest even in the last days of his life.Jiří Pauer was an optimistic soul. He sometimes clashed mightily with the “stupidity” of the powerful, always aware that the struggle must go on continuously. “If you achieve five percent of what you set out to do, you are successful,” he told his students. We can safely say that in his organizing activities as well as as a teacher and a composer, Jiří Pauer “achieved” a great deal more than that five percent.

Author: Otomar Kvěch

E-shop Českého rozhlasu

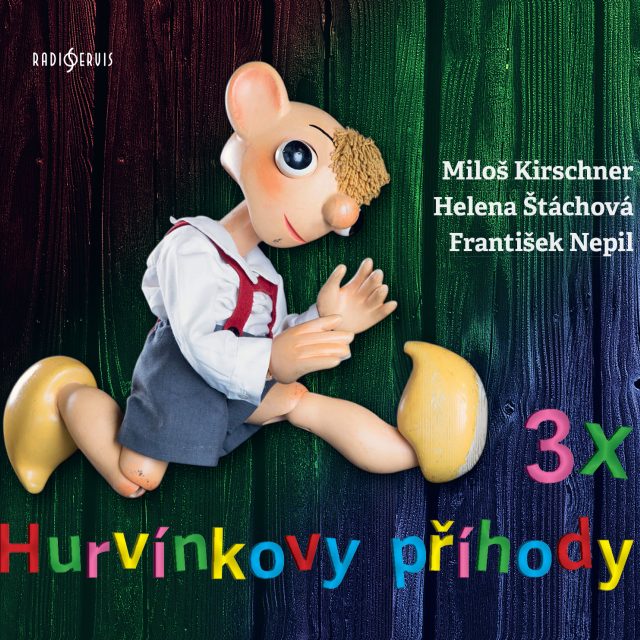

Hurvínek? A od Nepila? Teda taťuldo, to zírám...

Jan Kovařík, moderátor Českého rozhlasu Dvojka

3 x Hurvínkovy příhody

„Raději malé uměníčko dobře, nežli velké špatně.“ Josef Skupa, zakladatel Divadla Spejbla a Hurvínka