Alois Hába

*21 June 1893 Vizovice†18 November 1973 Prague

“Often just raising the apex of a melody by a mere half-tone, a quarter-tone or a sixth-tone, just prolonging or shortening a certain passage by a single beat, just livening up or rearranging the rhythm will be enough to achieve some satisfactory musical expressivity. This work is like polishing a precious stone. Perfect polishing increases its value. And only the ability to do such polishing guarantees composers perfection in their creative work and certainty in their ability to evaluate their own work and that of others.” It was with these words that Alois Hába introduced a concert of works composed by himself and his students on 13 March 1945 in the Municipal Library in Prague. He had been teaching at the Prague Conservatory since 1923. Besides the followers in his own country, Hába at that time attracted students from southern Slavic countries (Slovenia and Serbia), from Bulgaria, Lithuania, Turkey even, and elsewhere. The Prague Conservatory and musical Prague in general enjoyed an international reputation, and a great deal of credit for that goes to the contacts and pioneering efforts of Alois Hába.

As Hába repeatedly stated, it was the music of his own native region that led him to the idea of enriching European musical language with smaller intervals than the half-tones that are usual in European music. Born in Vizovice, he perceived in the singing of his mother and the music making of his brothers, his father, and other folk musicians shadings of intonation that sounded “different” from the music he heard in school and church. He graduated from the teachers’ college in Kroměříž, and already there he found out from his textbooks that the European system of music was not the only one in the world and that even some European music had in the past used different scales than the ones used in his time. His decision to study composition came almost after he was an adult. He was accepted into Vítězslav Novák’s advanced composition class when he was twenty-one, but then World War I broke out, and Hába had to report for service. After some time he was able to return to the home front and to continue his studies with Franz Schreker in Vienna and in Berlin. Thus it was in Germany that he made his entry into the world of music as a composer. He soon came to be known as one of the most daring when his quarter-tone String Quartet No. 2 was performed in November 1922 at the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin, this being his first work written consistently in the quarter-tone system. Then in July of 1923 at the festival of modern music in Donaueschingen, the Amar-Hindemith Quartet played Hába’s String Quartet No. 3, it too a quarter-tone work, and his name began to appear alongside other representatives of his generation’s avant-garde musicians. The ISCM (International Society for Contemporary Music) was founded in Salzburg in 1922, and Czechoslovakia became one of its first member countries. In 1923 Alois Hába returned to his homeland and immediately involved himself in new activities. In 1924 Prague served as the host city for the orchestral part of the ISCM festival, and as one of the sideline events of the festival Hába presented his quarter-tone piano, which had been constructed to his specifications by the August Förster company of Saxony in their Czechoslovak branch in Jiříkov.

Quarter-tone music, Hába was convinced, would represent a major enrichment of European musical language. In the following years he wrote a series of articles and textbooks on harmony. He explained his system and offered practical examples in his compositions and in the conservatory, where he introduced it to the students in his composition courses. The high point for Hába was the 1930s: early in that decade, on 17 May 1931, Munich heard the premiere of the world’s first and still to this day only quarter-tone opera, Matka (Mother). It was also the early 30s that saw the writing of what is probably Hába’s most important orchestral work, the symphonic fantasy Cesta života (The Path of Life). The 1930s also shaped Hába’s political stance and philosophy of life. His strong sense of social commitment found an intellectual basis in the Anthroposophical teachings of Rudolf Steiner.

During the war Hába wrote a continuation of his Theory of Harmony, completed a sixth-tone opera (never produced), and considered constructing a twelfth-tone harmonium. For the first time he used the solo harp in his compositions, and he was much taken by the guitar although up until that time he had never written any music for it. One proof of the authority Hába wielded is the fact that after the war ended, young theatre professionals chose him as heard of opera section of the Theatre of the Fifth of May, which took over the building of the former New German Theatre. After 1948, however, the theatre (now as the Smetana Theatre) was combined with the National Theatre. Hába was dismissed, and his department of microinterval composition at the Academy of Performing Arts, which had been founded in the post-graduate school of the conservatory, was dissolved. Between 1948 and 1950 Hába tried to comply with the officially imposed aesthetics of social realism and composed nothing but pro-socialist songs and choruses. Still he was unable to rid himself of the label of “formalist” stuck onto him by Marxist aesthetics. In 1953 he was sent into retirement, but in his own words it was only at that point that he achieved real creative freedom. In 1956 he was invited to the Darmstadt Summer Courses. In 1957 he was named an honorary member of the ISCM. In 1967 the ISCM again held its festival in Prague, and for it the Novák Quartet performed Hába’s String Quartet No. 16, composed in fifth-tones.

. All three areas of Alois Hába’s activity – composing, teaching, and organizing – evince one of his fundamental characteristics: the courage to move into a territory where no one else had thus far dared go. Hába was not some kind of “microinterval fanatic” as is sometimes assumed. He did offer his students this path, but he never compelled them to travel it. He was an example of musical perseverance, and although the worldwide universal musical language which he strove to create proved to be a utopia, his importance for the development of music in the 20th century is unparalleled.

Author: Vlasta Reittererová

E-shop Českého rozhlasu

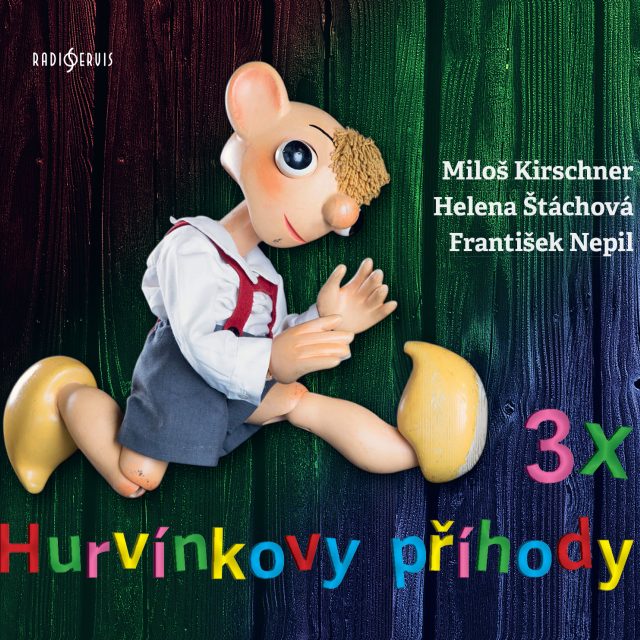

Hurvínek? A od Nepila? Teda taťuldo, to zírám...

Jan Kovařík, moderátor Českého rozhlasu Dvojka

3 x Hurvínkovy příhody

„Raději malé uměníčko dobře, nežli velké špatně.“ Josef Skupa, zakladatel Divadla Spejbla a Hurvínka